Diplomacy: A Discussion in Three Parts (2/3)

/Whilst historical recording is one way you can affect leadership opinion regarding foreign policy, protest is another form of civilians shaping political opinion.

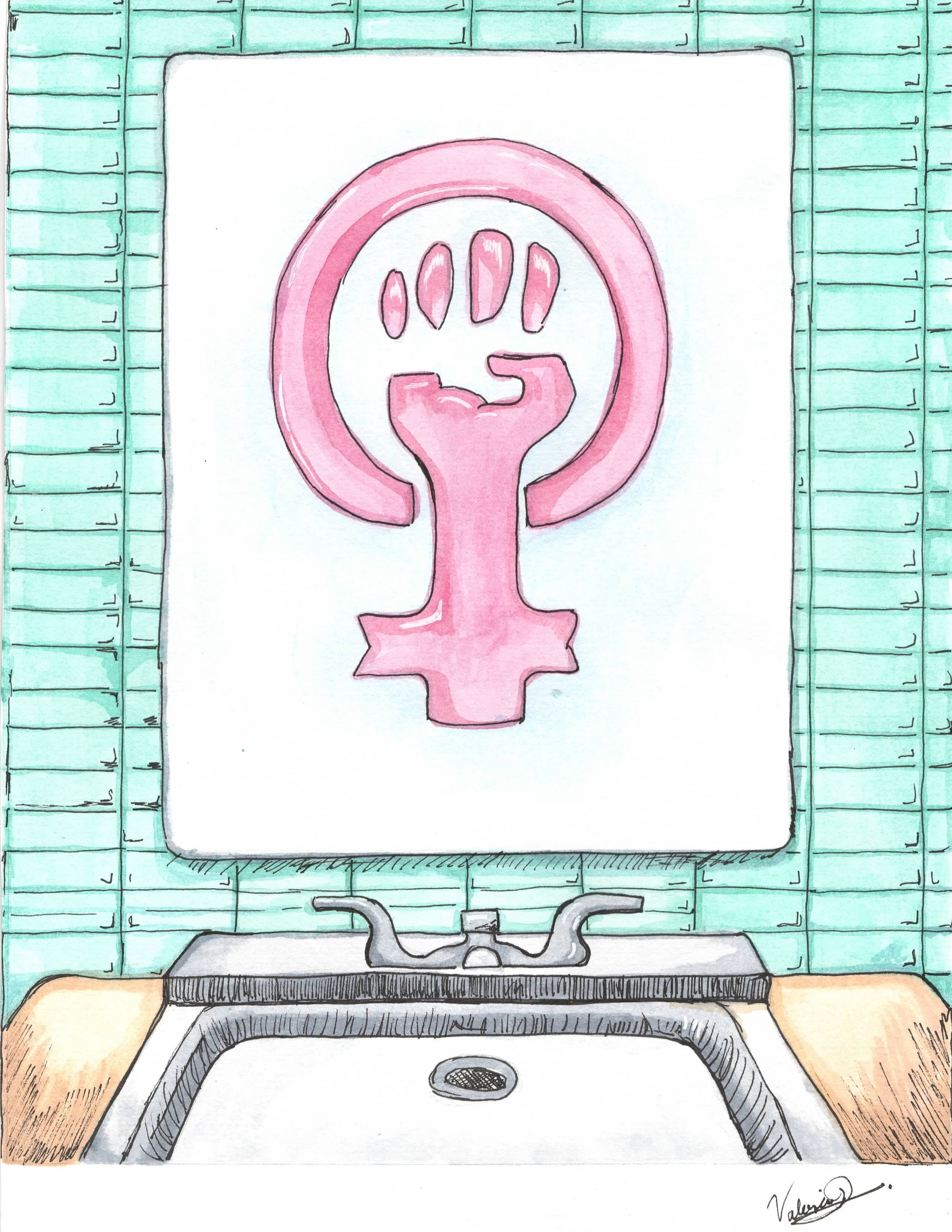

Through the painting “Hidden Protests”, Valerie comments on a silent protest held by students on 8th March in her school where girls would place secret notes around the school to comment on the issues surrounding violence against women in Mexico. The concept of a travelling message and composition reminds me of a poster and the visual of the women’s right symbol on the surface a mirror above the sink looks like she’s encouraging the viewer to look at themselves through the symbol. As if asking the viewer, put yourself in the shows of the protesters, join the conversation. A call to action on a human rights level that requires the attention of policy makers. The simplicity of the artwork and considering that messages have been popping up at her school may encourage others to do the same and bring the attention of those in a higher position like social media and, considering the message has reached the UK through the competition, it also showcases the importance of sharing art as a form of expression and gets more attention on a sensitive topic that civilians and children in school want support from their leaders on.

The importance of civilians in shaping foreign policy and diplomatic relationships can also be seen by the Zamthingla Ruivah’s Kashan pattern which was woven all over India as a protest against the legal immunity of British soldiers in India in regards to violence against indigenous women and children. This helped to get the Indian government to develop a new foreign policy against British soldiers who held certain legal protections like not being punished for civilian crimes like murder as victims were considered casualties of conflict. The Kashan is a piece of fabric that is worn like a Sarong worn by the indigenous population of southern India and when a teenage girl was killed for not wanting to leave her home to go with soldiers in 1986, Zamthingla made a weaving pattern in her honour as a protest as she was her neighbour and a fellow weaver. The movement caught on around India in non indigenous areas too and many Kashan’s were woven and flown like flags in marches and community weaving projects and finally the soldiers were charged with the murder of Luingamla. The laws surrounding foreign soldiers were changed because of that case and shows the power of civilians and cultural traditions and arts in shaping relationships with other countries.

Valerie’s and Ruivah’s work both comment on the underground movements that spread messages to bring communities together. These acts are often the beginning of social revolution and the purpose of that is to maintain the community balance. Whilst these works are more focused on the concept of violence against women and children, the use of collaboration can be used to comment on a multitude of social issues. How can you use craft in a collaborative way to share a message on conflict? It doesn’t have to be a textile. Maybe make a poster with other people and ask others to paint their version of it and start a movement? Maybe do a group project where everyone draws their version of the perfect future? Remember this year’s competition question asks you “How can we prevent future wars?” Diplomacy takes effort from all sides to come up with a relationship that benefits everyone and reduces international conflict. You never know who may witness your work and how they can impact the policies that affect the social and international issues that you have a problem with…

Next week’s final diplomacy post will look at the actual international portion of diplomacy and we’ll be comparing a really impactful work in our archive compared to a great piece in the National Gallery.

Further Reading:

What causes Huntington S. P. (1968) Political order in changing societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

Marshall, T. (2016). Prisoners of geography : ten maps that explain everything about the world. New York, NY: Scribner.

Violence against Women in Mexico: United Nations (2023). ‘We’re here to tell it:’ Mexican women break silence over femicides. [online] OHCHR. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2023/07/were-here-tell-it-mexican-women-break-silence-over-femicides.

Indigenous women’s rights group in Manipur India who helped get soldiers punished for the death of Luingamla: Tangkhul Shanao Long (TSL) (2024). Uniting Women for Justice - Tangkhul Shanao Long (TSL) -. [online] Tangkhul Shanao Long (TSL) - Enhancing women’s potential. Available at: https://tangkhulshanaolong.com [Accessed 15 Jan. 2025].

Abdel-Fattah, R. (2016). When Michael met Mina. Sydney, N.S.W.: Pan Macmillan Australia.

Amnesty International (2015). We are all born free : the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in pictures. London: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Camerini, V., Carratello, V. and Moreno Giovannoni (2021). Greta’s story : the schoolgirl who went on strike to save the planet. New York, Ny: Aladdin.

Margolin, J. (2020). Youth to power : your voice and how to use it. New York: Go, Hachette Books.

Pascoe, B. (2019). Young dark emu: A truer history. Broome, W.A.: Magabala Books.

Rich, K. (2018). Girls resist! : a guide to activism, leadership, and starting a revolution. Philadelphia: Quirk Books.

Thunberg, G. (2019). No one is too small to make a difference. Uk: Penguin Books.