Education: Public Art Teaching Public History

/Art in regards to education is intrinsically linked to public displays; whether that be sculptures, murals or graffiti in high foot traffic areas. Public art addressing war and conflict serves as a medium for remembrance, education, and social commentary, providing perspectives that commemorate sacrifice, question political motives, and explore the human cost of violence. Administrations like local councils or a Ministry of Culture would usually handle organising these as usually topics are culturally sensitive and need checking to make sure the pieces pay the proper respect and attention to its “Homage”. Today we’ll discuss both 3D and 2D art and invite you to consider how your artwork can be educational to others.

Angela, 16-18, USA, who are war [acrylic and carboard sculpture], never such innocence archives

Angela’s sculpture, “Who Are War?”, is a striking installation that occupies public space to create an immersive, thought-provoking experience. The central figure—a head constructed from cardboard and painted with acrylic—wears a gas mask, instantly evoking imagery of a soldier bracing for the harsh realities of conflict.

Set within the confines of a fence, the sculpture’s placement and materials create a visual tension that feels simultaneously protective and hostile. Through this juxtaposition, ‘Who Are War?’ powerfully highlights the duality of war—resistance and survival alongside confinement and aggression. The piece not only reflects the soldier’s need for resilience but also reveals the psychological toll of being both protected and restricted by the mechanisms of warfare.

By placing her work in a public setting, Angela invites viewers to confront the realities of conflict and reflect on its human cost, with the raw, hand-crafted appearance of the sculpture contrasting starkly with the industrial fence to highlight the harsh blend of vulnerability and strength needed to endure war.

If you create a mixed media piece for this year’s competition, have you thought about using hard materials like metal wire with a softer material like fabric or tissue paper to capture tension like Angela has in her piece?

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wall of Oil Barrels—The Iron Curtain, Rue Visconti, Paris, 1961-62, Photo: Christer Strömholm / Strömholm Estate, © 1962 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Angela’s artwork reminds me of the iconic artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude. You might know them for wrapping famous buildings worldwide, like the Arc de Triomphe in France. Their public art is designed to make a big social impact.

One of their early works was ‘Wall of Oil Barrels: The Iron Curtain.’ This piece involved stacking oil barrels, with all their logos and rust, to block a small road in the Paris Left Bank. It symbolised the real-life ‘Iron Curtain’ that had been built in Berlin a year earlier. The installation disrupted a busy pathway, making people frustrated—not only with the artwork but with the political divide it represented between East and West Berlin.

While Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work is large and physical, it might be difficult to create something so big alone. Consider working in a group or making a proposal artwork to show what your art would look like in the intended space. This can still help you express your ideas in a powerful way.

mason, 11-14, usa, death’s reaper of war [graphite drawings and paper collages on a cardboard stand], never such innocence 2024/25 Competition entry

Another 3D artwork in our collection with a strong intended public impact is ‘Death’s Reaper of War’ by Mason. This miniature scene shows the intense effects of hyper-consumerism of media, with several billboards featuring powerful images. The piece is a bold reminder of the connections between war, power, and the destructive side of consumerism as it depicts “an image of Vladimir Putin’s face, split between his human form and a skull, symbolising the Grim Reaper” and “various symbols of war, such as a firearm, a grenade, and a human eye reflecting a nuclear explosion.”.

The work is intended to shove the artist's political viewpoint in your face. The large scale intent of the billboards dwarfing the size of the building means we can imagine the cars passing the signs and still noticing the sign from ages away. Therefore the intended visual impact lasts further than just the first view.

from “Truisms” (1977–79); Inflammatory Essays (1979–82), 1984

Offset posters, Installation: Poster Project, Seattle, Washington, USA, 1984, © 1984 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Jenny Holzer is another artist who uses her work to make bold political commentary. Her style tends to be very direct, as you can see in her ‘Inflammatory Essays’ installation, which was displayed in Seattle, Washington, in 1984. While Holzer uses a poetic style, her writing doesn’t follow a rhyme or rhythm, giving her work a straightforward, almost raw feeling.

This installation covered a large wall in a busy area, so it caught the attention of many people passing by. To make her message stand out, Holzer used different colours to separate sections of the wall, making people read each colour again and again until they realised each section repeated the same message. This strategy kept viewers focused longer, with her words gradually sticking in their minds. Even after they left, they would still be thinking about what she had to say, which was her goal—to make people truly engage with and internalise her political commentary.

Like Mason’s work, Holzer’s message remains with the viewer, encouraging them to think deeper about the issues long after they’ve walked away.

sadie, 14-16, thailand, ties that bind [pen, pencil, crochet], never such innocence archives

Ties that Bind by Sadie (14-16, Thailand) is a multi-media artwork, and also a great example of how public art can raise awareness and educate people. Sadie, who moved from New York to Thailand, says she doesn’t want to forget big events that plagued her community when she lived in New York, especially the 9/11 tragedy. She believes that, “although we move on now, we will never forget.”

The experience of living through the aftereffects of 9/11 stayed with her. Sadie used crochet to link different parts of her artwork, symbolising “connection—something that surfaces after every conflict.” Her themes of connection and remembrance help raise awareness. Drawings of vigils (memorial gatherings) that took place all over New York after 9/11, along with the “ties that bind,” look like a map of the city, reminding (“educating”) people of the connections that form in times of tragedy.

Try it yourself : Mixed media artwork combines various materials like paint, fabric, and photographs, creating rich textures and layers of meaning.

By blending different elements, Sadie explored multiple themes in a single piece, inviting viewers to interpret how these materials interact. This dynamic approach encourages curiosity and adds depth to the artwork.

United Nations. (n.d.). Guernica Tapestry by J. de la Baume-Durrbach and Pablo Picasso at United Nations Headquarters. [Tapestry]. UN Conference Building, New York.

In regards to art as historical records, the Guernica tapestry in the UN, based on Picasso’s painting, depicts the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. Based on the original painting by Picasso, the tapestry was supervised by the artist himself at the Atelier J. de la Baume-Durrbach and kept in the home of Nelson Rockefeller, whose wife, Happy, lent it to the UN in 1985.

This artwork's multiple lifetimes, first as an oil painting and then as a weaving served as a medium that educates the public on specific historical events, providing a visual reminder of one of the first cases of purposeful civilian bombings. Especially considering its current location - the impact of its education reaches further since it’s on a platform that maintains international peace and security.

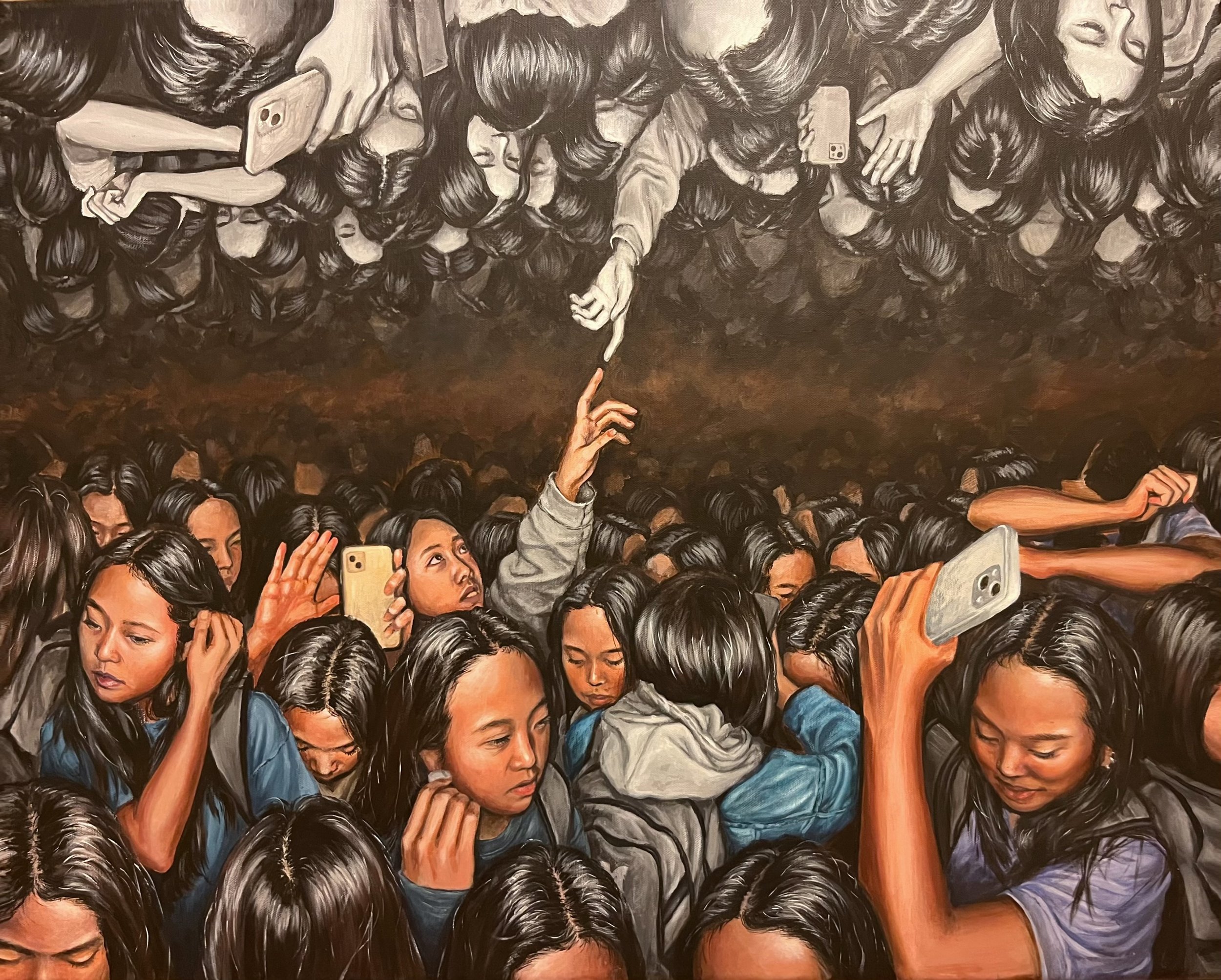

Ke, 16-18, usa, then and now [colour pencil and graphite], never such innocence archives, london, (photo © never such innocence)

Yutong’s artwork “Then and Now” serves to be a mirror on society after conflict. “The crowd of people represents while scars remain, life still moves on, and time is fleeting.” She encourages you to turn the artwork upside down and see the range of colour and emotion. The crowd work between the black-and-white section and the colour section centres the emotional context of the piece.

The faces are much more hidden in the monochrome half while the joyous colourful half seems more alive. As you look further, the poses are mirrored in most of the figures suggesting that the figures are stuck in the situation from the side. But what came first, the colour or the shadows? The ambiguity allowed for Yutong to further her aim to show how the effect of conflict persists during and long after conflict.

This piece especially reminds me of Rivera’s work where he depicts the struggles of Mexican society through these crowd-focused compositions that showed a shared struggle to remind people that they are not the only ones who experienced and remember the horrors of the war.

Diego Rivera, Third Floor Murals, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1923–1928, Mexico City, Mexico. © Diego Rivera, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The social side of public education is shown well by Diego Rivera’s murals in the Mexican Secretariat of Public Education building. Rivera and a team of local artists painted over 128 panels between 1923 and 1928.

These murals used archival* techniques Rivera learned from studying art in Europe. This was important because the murals were made to teach people for many years about Mexico’s history, including its colonisation by Spain and later conflicts with the United States.

* This means the artwork will last a long time due to the chemical properties of the art materials used in the murals. If you want to read further the techniques are called Buon Fresco but there are more types of frescoes and murals if you want to try you hand it.

The idea behind the murals wasn’t just about art. José Vasconcelos, Mexico’s first Secretary of Public Education, hired Rivera because he wanted to improve education for many Mexicans. He believed art was a language everyone could understand, so he used these images to help educate people.

On the outside walls, the murals show everyday Mexican workers, like flour millers and weavers, to make people feel welcomed. Inside, the murals focus on bigger topics, like the growth of industry in Mexico and the hardships faced by native Latin Americans, to let people get immersed in the darker history of their Country; very appropriate for an education hub.

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, Non-Violence, 1980, United Nations Collection, Plaza at the UN Visitors Entrance, New York. © Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd Estate

War-related public art can stir up a range of reactions, with different people seeing it as patriotic, tragic, or even controversial. For example, the “Non-Violence” sculpture—a gun with a knotted barrel—has sparked debates about its message and placement, as some view it as a call for peace while others see it as politically charged. These varied reactions show how public art about war often reflects deeper societal values and political views, making it both a mirror of public opinion and a conversation starter.

Where would you like your work to be shown to have the biggest impact in order to answer the question “ How Can We Prevent Future Wars?”.

In conclusion, public art about war and conflict is a powerful way to connect us with important stories from the past and present. From memorials that honour the bravery and sacrifices of people affected by war to artworks that question the reasons behind conflict, public art brings these big issues into our everyday spaces. It helps us remember, think critically, and see the human side of history that’s often left out of textbooks. As the world changes, public art continues to challenge us to learn from the past and imagine a future with more understanding, compassion, and peace.

Honourable mentions of war based public art around the world:

“Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red” (poppy installation at the Tower of London, commemorating WWI casualties).

“The Fallen” by Jamie Wardley and Andy Moss, a beach installation representing the 9000 lives lost from both sides in the D-Day landings.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., designed by Maya Lin, as a space for healing and remembrance.

Warsaw Uprising Monument in Poland, symbolising the resilience of Polish resistance against Nazi forces.

Further Reading:

Christo & Jean Claude - Wall of Oil Barrels, The Iron Curtain : https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/the-iron-curtain/

How to make proposal artwork - Christo & Jean Claude - The Gates : https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/the-gates/

Jenny Holzer and her “Inflammatory Essays“ - 5 ways Jenny Holzer brought Art to the Streets : https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jenny-holzer-1307/5-ways-jenny-holzer-brought-art-streets ; Individual Pieces : https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/holzer-inflammatory-essays-65434/11

Picasso’s reimagined Guernica tapestry by the Atelier J. de la Baume-Durrbach at the UN:

Megan Flattley, "Diego Rivera, third floor murals of the Secretaría de Educación Pública," in Smarthistory : https://smarthistory.org/diego-rivera-third-floor-murals-secretaria-educacion-publica/.

Suzanne Lacy’s ideas on the New Genre Public Art movement that took over the art installation community : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/235298.Mapping_the_Terrain (if your library doesn’t have it, ask for an interlibrary loan if possible)

Interesting history of Barbed Wire for those interested in Angela’s “Who Are War?“ piece : https://digventures.com/2014/07/barb-aric-a-brief-history-of-barbed-wire/

Ways to get your community involved in your project : https://mymodernmet.com/andy-moss-jamie-wardley-the-fallen/